My Jane Austen Year

My Jane Austen Year

It was September 1996, and I had just started my first year of teaching. I had landed in Thomaston, Georgia at a time in my life when everything seemed to be going wrong. I was 22 and had no idea just how often things would veer from my idealized plans.

The fantasy? I would be seriously dating my college boyfriend with whom I was completely smitten. After graduating from the University of Georgia in June of 1995, I would begin a graduate program in clinical psychology somewhere in the southeast so that I would be within driving distance of my very-important boyfriend. I would distinguish myself as a bright, serious student with revolutionary insights into the field of psychology and clinical practice. All of my obsession with making A’s in all of my classes, getting research experience, and doing an internship would have dovetailed perfectly into this well-crafted plan. I would be fulfilled, in love, and very happy.

The reality? I did graduate in June of 1995. That much was accurate, but I had not been accepted to any of the clinical psychology programs to which I applied. (I had chosen the most competitive field of graduate study in psychology because if I worked hard enough, I could do anything. After all, my mother had told me so.) After an extremely brief tenure at the Department of Family and Children Services, a longer tenure working at a local gift shop through the holiday season, and a very interesting period working at a psychiatric hospital in Atlanta, I had taken a job teaching children classified as “severely emotionally disturbed.” For this, I would be paid “good money,” compared with the one hair above minimum wage I earned at the hospital. Plus, I could fix all of the disturbances in all of my students because I was Wonder Woman.

What happened to the very important boyfriend, you ask? I apparently wasn’t very important in his life. I was heartbroken but determined to recover. I applied again to graduate schools. I had taken the Kaplan course and raised my GRE scores ever so slightly, hoping that would do the trick. This would be a sort of gap year. I would get an apartment in Macon and commute the 50 miles to Thomaston. I’d hang out with my friends who were still in town and visit Atlanta some. The year would fly by.

I started my teaching job days after leaving my job at the psychiatric hospital before I had even finished moving my belongings from Atlanta. I had never taught before, (My mother was a teacher, and I had sworn that I would never teach. Never say never.) but my new employers said that was no problem. If I could do physical restraint (I could.) and manage the kids’ behavior (Of course.), then I could figure out the teaching. No big deal, right? I had attended elementary school. How hard could it be to teach in one? (Insert ominous music or maniacal laughter here.)

One evening, during the pre-planning days, I was pacing back and forth in my parents’ kitchen talking on the wall phone when my knee popped out of joint, and I fell to the floor. That’s right, talking on the phone, not water skiing or hang gliding or playing frisbee. After hobbling around on crutches for a few days and having my mother drive me the 50 miles back and forth to work, I saw a doctor who said that I would need outpatient surgery. So, on the first day for the students, when I had planned to be establishing perfect order and starting to cure all of my students’ problems, I was having arthroscopic knee surgery instead.

A week later, I was getting around pretty well, had been cleared to drive, and was only keeping crutches handy for emergencies. It was time to go back to school and meet my class for the first time. I only had one job to perform versus the two jobs I had been expected to do at the psychiatric hospital, and I had an assistant. I could do this. And then I met the students.

At the psychiatric hospital where I possessed so much behavioral expertise, I worked on a locked unit with a nurse. If an emergency arose, we could “call a code,” and a team of people literally came running to help. At my new gig, my classroom was in a run-down building on the somewhat deserted campus of an alternative school with many exits, no locked doors, and I was barely ambulatory. One of my students had been described as a “runner,” meaning that she ran away at the drop of a hat—and she was fast. The second child had been removed from his home due to extreme abuse and neglect and had a multitude of emotional and physical problems, not the least of which was encopresis. If you do not know what that is, be very glad. It means that a person defecates in his or her clothing or basically anywhere besides a toilet. The third child was poised to transition back to his regular school and was supposed to be “easy,” but he was none too impressed with me. For one thing, I had no idea how to teach and, worse, I was not Ms. Cathy, their beloved teacher, who was not returning. The students held me personally responsible for this.

Seven exhausting school days followed during which Sally ran away—or threatened to—daily. Adam stood by my desk every morning grimacing and farting right over my coffee, while I wondered whether they were more than farts. Michael refused to do anything unless my teaching assistant asked him to. You could say that this was an exercise in humility.

Then came the straw that broke the camel’s back, me being the camel in this scenario. I had a head-on collision on my way to school. Because of the 50 mile commute, I had to leave home in the dark in order to arrive at school on time. On this morning, I was driving along listening to Hootie and the Blowfish’s “Only Wanna Be with You” when I saw headlights coming toward me in my lane. I swerved to avoid them, but they followed, and we collided head on. (There is much more to that story, but that’s another essay entirely.) In a nutshell, I was not seriously injured. The passengers in the other car were okay, but one required emergency surgery. My car was totaled, of course, and I was out of the classroom again.

I typically do not give up easily, but after the accident, I lay in bed and cried for two solid days. I cried about the accident, about the job at which I felt so inept, about my lost car, about my rejections from graduate school, and about the break up with my boyfriend. My parents told me that I could quit the job and, for about a day, I considered it. The prospect of staying at my parents’ house with no job was no more appealing than returning to my class wounded and broken, somewhat like the children whom I was charged with teaching. My woes were still very much first-world problems. Even in my funk, I could recognize that.

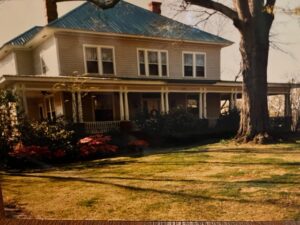

I went shopping for a new car and gave up the apartment in Macon. My mother rescued me again and took me all over Thomaston looking for places to live. I no longer wanted to commute 100 miles round trip every day, and I certainly wanted to avoid passing the site of my recent accident. We had struck out with apartments when we decided to stop at a bed and breakfast just off the town square. I immediately loved the wrap-around porch with rocking chairs and the gorgeous oak tree from which the bed and breakfast got its name, The Grand Oak Inn. I don’t remember precisely how it transpired now, but we struck a deal with the owner that I would rent a room during the week for a discounted rate and vacate the room on the weekends when she needed the space for other guests.

What a lift I felt when I saw the spacious room with hardwood floors, high ceilings, and a lush four-poster bed just for me! I’d come in each afternoon, exhausted from teaching, and find my bed made and, every couple of days, there would be fresh towels, and specialty soaps and shampoos in my bathroom. Every first-year teacher should be so lucky! For the first few months, I would fall asleep in my clothes every evening watching “Who’s the Boss?” re-runs, not even waking up to eat supper, get up the next morning, and do it all again.

Over Christmas holidays, my dad took me to the expansive two-story Borders bookstore across from Phipps Plaza in Atlanta. I found a hefty collection of all of Jane Austen’s novels there. I had been wanting to read them, and what better time to do just that? A wounded heart, social isolation, and a gorgeous old house seemed the perfect conditions for me to tackle the reading of Jane Austen’s works, and tackle them I did. After school, instead of flopping on the bed, I would go out to the porch and immerse myself in the world of the Bennet sisters, the Dashwoods, Fanny, and Emma. Pride and Prejudice was my favorite and, though my college beau was no Mr. Darcy, I did see some parallels between my life and Elizabeth Bennet’s. It seemed that my former boyfriend found my “relations” beneath his well-heeled Atlanta upbringing. I cringed sympathetically when I read the passages about Lizzie’s family. I longed for one of Elizabeth Bennet’s razor-sharp retorts when I remembered my boyfriend suggesting that I have electrolysis done on my eyebrows. How had I thought that I was so lucky to be regarded as a fixer-upper? I felt empowered when Elizabeth held her own against Lady Catherine De Bourgh. I marveled at how little things had changed since Jane Austen’s time when Lady Catherine said to Elizabeth, “If you were sensible of your own good, you would not wish to quit the sphere in which you have been brought up.” And then I found Elizabeth’s response to be a triumph: “In marrying your nephew, I should not consider myself as quitting that sphere. He is a gentleman; I am a gentleman’s daughter; so far we are equal.” I wished I had been as courageous as Elizabeth in defending my family.

Jane Austen’s keen observations about people, her pitch-perfect dialogue, and her courageous voice were a salve to my wounded pride and, slowly, I began to hope that my true Mr. Darcy was yet to be discovered.

Over spring break that year, my parents took me to England and indulged what had become my full-fledged obsession with Jane Austen. We went to Chawton and saw the table where she sat and wrote her novels. We took a turn in the garden where the daffodils were in full bloom. We visited Bath, which I tried to imagine in the height of the social season, and we went to Winchester to see where Jane Austen was buried.

I realized that my “relations” were far from unfortunate; they had bolstered me and restored my hope and spirit in every way that they could. Though I would never want to relive that year or the difficult lessons it brought, I do remember with fondness the many afternoons I spent on the side porch of the Grand Oak Inn, slipping from the heartbreaking world of my students and the uncertainty of my future into a safe beyond where Jane Austen drew me into her characters’ lives and ushered me through the tumult of my own.